Changing rangatahi lives in Te Awamutu

Photo: Hauora Team Leader Vinnie Ngaruhe, General Manager Georgina Christie and Raven Torea of Whānau Voice.

Recently, our Whānau Voice kaimahi spent time with Ko Wai Au Trust, a kaupapa Māori rangatahi service grounded in the belief that when young people know who they are, where they belong, and are supported to shape their own futures, they can thrive.

Established in March 2023, Ko Wai Au has grown quickly in response to the needs of rangatahi aged 15 to 24 across Te Awamutu and surrounding communities. Guided by a clear vision to empower rangatahi to live confidently and independently, the Trust places strong emphasis on identity, belonging and practical pathways forward. Its Hauora service, launched under Pinnacle, reflects this by providing accessible, culturally safe health and wellbeing support for rangatahi and their whānau.

Ko Wai Au works closely with rangatahi in schools and in the wider community, often supporting young people who are navigating multiple challenges at once. Their approach centres on early support, strong relationships and walking alongside rangatahi over time. Kaimahi meet rangatahi where they are, building trust and creating space for honest conversations about what is getting in the way of wellbeing, learning or stability.

Support is holistic and rangatahi-centred. Advocacy and mentoring help rangatahi move into education, training and employment, while also supporting them to navigate health, social and justice systems when needed. The team includes youth workers and addiction counsellors who deliver one-to-one support, group programmes and health promotion initiatives that normalise conversations about mental health and reduce stigma.

Much of the mahi focuses on breaking “revolving door” cycles that can keep rangatahi stuck. Practical support with driver licensing, re-engaging in education, first aid certification, life skills and goal-setting helps young people build confidence and independence. Current programmes include Mana Whatu Ahu for rangatahi still engaged in schooling, Tama Ora Tama Tū for those not currently at school, Tu Mahi Toi, walking groups and kai education. Transport is also provided, removing a major access barrier for many rangatahi and whānau.

Strong relationships with local schools underpin the mahi of Ko Wai Au. Trusted partnerships with Cambridge High School, Te Awamutu College and Cambridge College enable early identification of need and coordinated support. Whānau engagement is another strength.

Many parents are working long hours, and a significant number of rangatahi come from low socio-economic households. Ko Wai Au estimates that around 75 percent of the rangatahi they support lack positive role models, making consistent mentoring and trusted adult relationships especially important.

Ko Wai Au also collaborates widely across the local system, including with Rural South mental health services, local GP practices, Cambridge Community Hub, Youth in Tech, and mana whenua partners Ngāti Korokī Kahukura and Maungatautari Marae. These relationships enable rangatahi to access the right support quickly and in ways that feel safe and culturally grounded.

Despite their impact, funding insecurity and housing instability remain significant challenges for rangatahi and for the service itself. From a Whānau Voice perspective, Ko Wai Au demonstrates what works. Kaupapa Māori, relationship-based support that strengthens identity, builds belonging and supports rangatahi to become confident contributors to their communities. Sustainable funding and fair access to commissioning will be critical to ensuring this mahi can continue into the future.

ACC-recognised rongoā in our rohe

Photo: Raven Torea with Whāea Lynette Stafford

Healing grounded in aroha and intention sits at the heart of rongoā Māori. As the whakataukī says, He ringa nā Rongo, he ringa nā te aroha, the hands that heal are guided by peace and care.

The Whānau Voice team recently spent time with rongoā Māori practitioner Lynette Stafford, gaining insight into a healing practice that weaves mātauranga Māori with contemporary therapeutic approaches.

Lynette, known to many as Whāea Lynette, is a rongoā practitioner working through her organisation Te Kora O Mahuika, a Waikato-based provider covering Te Awamutu, Kāwhia, Te Kūiti and Hamilton. Her work takes her across the rohe, and she is in high demand, supporting whānau with injury recovery and wellbeing.

Around 96 percent of Lynette’s mahi is funded through ACC referrals, reflecting growing recognition of rongoā Māori as a legitimate and effective pathway for healing. ACC currently supports rongoā as part of injury recovery, and Lynette is formally trained through Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, where she completed her rongoā qualification. She is also trained in the Emmett Technique, a specialist muscle release therapy that uses gentle finger pressure on specific points of the body to support physical recovery.

Lynette explained that the Emmett Technique is suitable for addressing a wide range of physical and non-physical injuries, and that practitioners must be formally trained to apply it safely. In her practice, this technique often sits alongside rongoā Māori, including rongoā rākau, where native botanicals are used as part of healing. These plants are carefully sourced and applied with knowledge handed down through generations.

For Lynette, rongoā is never “just one thing”. She shared that people sometimes think rongoā is only mirimiri or karakia, but in reality it is a holistic system of healing that includes different forms of treatment, spiritual care, physical techniques, plant knowledge, and deep connection to whenua and whakapapa. In Waikato alone, there are a small number of trained practitioners, each carrying distinct knowledge and approaches.

The visit was especially meaningful for Whānau Voice kaimahai, Raven, who is also a nursing student. Seeing how rongoā Māori and techniques like Emmett can sit alongside Western health practices was new to her and highlights the potential for truly complementary care that centres whānau needs and lived experience.

Time with Lynette reinforced the value of kaupapa Māori healing approaches and the importance of creating pathways where whānau can access care that feels culturally safe, effective, and grounded in who they are. For Te Tiratū and the Whānau Voice team, this visit was a powerful reminder that wellbeing is relational, holistic, and deeply connected to whenua, mātauranga, and whānau.

Pinnacle PHO & Te Tiratū strengthen partnership

Photo: Amit Prasad, Justin Butcher, Glen Tupuhi co-chair Te Tiratū, Brandi Hudson Tumu Whakarae Te Tiratū and kaimahi Rawiri Blundell and Koro Samuels

With a shared commitment to improving Māori health, Te Tiratū Co-Chair and Tumu Whakarae met with Pinnacle Primary Health Organisation leaders Amit Prasad, Justin Butcher, and kaimahi Rawiri Blundell and Koro Samuels to strengthen collaboration on primary care in Waikato.

The kōrero emphasised the importance of all PHOs and Te Whatu Ora working together, particularly by aligning how health data is collected and reported, so decisions are based on accurate, timely information that truly reflects Māori communities at both regional and local levels.

Pinnacle PHO supported our Position Statements and concerns about vaping and its long-term impact on rangatahi and whānau, the critical role of school nurses in proactive healthcare, and the particular challenges faced by rural communities.

There was unanimous agreement that the high number of unenrolled Māori, and those enrolled but not receiving regular health checks or screenings, is an urgent issue that must be addressed collaboratively.

The discussion also highlighted shared pressures in the primary care workforce and the need for sustainable funding solutions. Expanding nurse-led models of care, including mobile services and workplace health checks, was seen as a practical way to reach Māori men and whānau, help address GP shortages, and reduce wait times for appointments.

Strengthening the link between primary care and specialist services was recognised as essential for managing long-term conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory illness, mental health, and gout, particularly improving access to prescribed medications. Greater use of Nurse Prescribers was identified as a key way to tackle this pressing equity challenge.

Both organisations acknowledged the importance of supporting whānau to navigate modifiable behaviours, including nutrition, exercise, alcohol use, smoking, and vaping, while ensuring health education resonates with young Māori.

They also recognised that many whānau cannot afford expensive healthy food options, and that solutions must be practical, affordable, and grounded in the lived experience of Māori communities. Lifting immunisation rates remains a shared priority, with a clear focus on closing Māori equity gaps before broader population initiatives.

To maintain momentum and deepen the partnership, a Board-to-Board hui will be scheduled in the New Year. This meeting will advance collaborative work on health data, strengthen advocacy, and guide future investment and planning to achieve better health outcomes for Māori across the Waikato.

Te Tiratū takes to the streets in Hīkoi for our Health

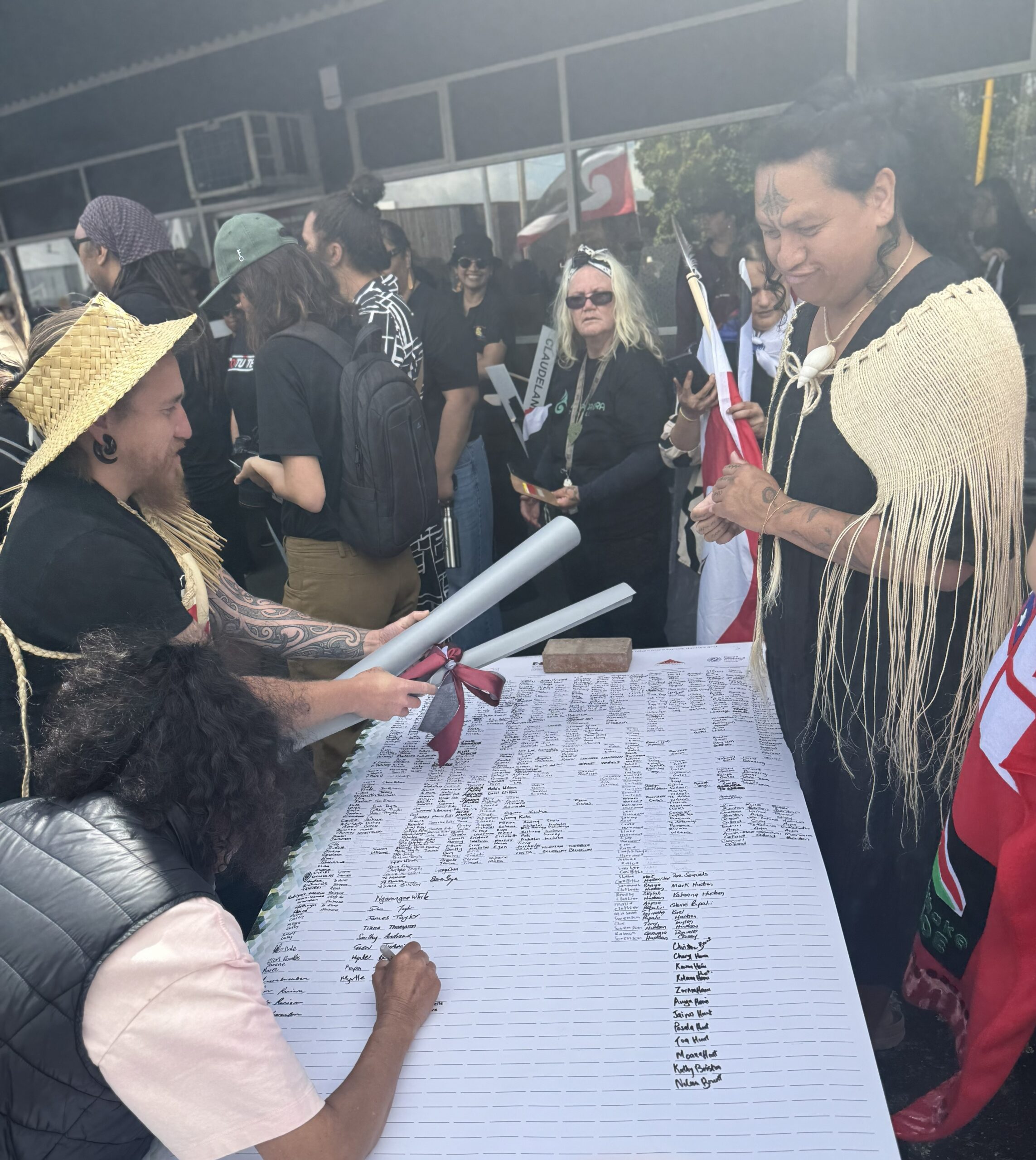

Several Te Tiratū board members with our senior executive walked in solidarity with hundreds of whānau in the Hamilton leg of the nationwide Hīkoi for Our Health, that’s calling for urgent government action to fix Aotearoa’s failing health system.

The march, led locally by Lady Tureiti Moxon, Managing Director of Te Kōhao Health, departed from Hamilton Lake Playground to Waikato Hospital carrying the Buller Declaration on the State of the New Zealand Health System, now signed by more than 95,000 people.

Our Co-chair Glen Tupuhi, reflected on the responsibility of older generations in protecting the health system.

“It’s very important when we look around and see the rangatahi, and also the baby boomers. It is us that are breaking down. It is us that are putting pressure on the health system, and it is us that really need to fight for the retention of services and not allow this creeping privatisation,” he said.

“Exposing health to free market forces is not going to be good for us, our children, or our tamariki. Our tupuna fought to build the welfare state, and we have inherited that. It’s up to us to ensure it is handed on to the next generation.”

Brandi Hudson, our Tumu Whakarae had a similar stance, “We are here because we want to celebrate the fact that Māori are leading the way with advocacy for better health services for our whānau. We thank Lady Tureiti Moxon today for working alongside the whānau or Kirikiriroa to highlight how the resources for Māori health are failing.”

The focus for Lady Tureiti Moxon is partnership and structural change.

“Te Tiriti o Waitangi is a blueprint for partnership and accountability. When the Crown makes decisions about Māori health without Māori, that is not partnership. We need structural change. This hīkoi is about calling the Government to honour Te Tiriti and build a system designed with, by, and for our people. We walk not just for ourselves, but for our tamariki and mokopuna. For our hauora. For our future,” she said.

Malcolm Mulholland, Chair of Patient Voice Aotearoa and the national organiser, said the hīkoi sends a clear message across the country.

“New Zealanders are united in saying our health system is in crisis. We walk for those behind the statistics, those waiting in corridors, those turned away, and the health workers holding the system together. This hīkoi is our call to those in power: fix it now, before more lives are lost.”

The month-long hīkoi, which began in Westport on 1 November, retraces the path of the original Buller march that sparked this national movement.

It will reach Parliament in Pōneke on Tuesday 18 November, where thousands are expected to gather to deliver the signed Declaration to Members of Parliament. Today in Kirikiriroa, the message was one of unity, mana motuhake, and hope for a health system that values people over bureaucracy and equity over excuses.

Hauora Day brings Cambridge whānau together

As the sunshine lit up Cambridge Community Marae, Ngāti Koroki Kahukura welcomed whānau, health providers, and our Whānau Voice kaimahi from Te Tiratū to celebrate Hauora Day.

It was a vibrant gathering of kōrero, connection, and community spirit. Organised by Norma Taute who we applaud as she has championed Hapu Hauora amongst Ngāti Koroki Kahukura. The event brought together Māori and non-Māori providers alongside whānau of all ages, creating a safe space to share stories, explore health services, and highlight both the strengths and gaps in care.

Providers shared insights into the needs of whānau, from understanding the difference between occupational and sports injuries versus age-related conditions with ACC, to the importance of alcohol and other drug support in and out of prison.

The kōrero revealed gaps in primary mental health care, challenges accessing cervical screening despite self-testing kits, and the ongoing need for hearing checks and oral health support for tamariki. Traditional rongoā practitioners, St John’s Ambulance, and suicide prevention teams were also part of the kaupapa on the day.

Whānau also shared their experiences, celebrating excellent hospital support while caring for loved ones, and highlighting disruptions when long-standing doctors retire. Across the 16 surveys completed on the day, whānau spoke of long GP and specialist wait times, the rising cost of healthcare, transport challenges, and the need for kaupapa Māori and holistic health services closer to home.

Activities that support wellbeing including whānau time, cultural connection, marae participation, and physical activity were identified as central to hauora. Almost all whānau who participated felt that government health and mental health targets do not meet their needs, reinforcing the importance of listening to whānau voices.

We gathered kōrero and ensured whānau perspectives were amplified alongside providers, making the day as much about listening as it was about sharing. On stage, Hauora providers showcased their services, a raffle was drawn as we all enjoyed a delicious, shared hangi.

Despite other events like waka ama taking place on the same day, Hauora Day was a clear testament to the commitment of Ngāti Koroki Kahukura to whānau wellbeing. It showed that whānau people come together to kōrero, share knowledge, and celebrate collective care, it strengthens not only their individual health journeys but the health of the whole hapori.

Te Awamutu Gala celebrates Hato Hone St John & hauora

Te Tiratū was proud to attend Te Awamutu’s annual Community Gala at Albert Park, held in support of Hato Hone St John and their ongoing commitment to our community. The gala brought together locals, visitors, businesses, supporters, and volunteers for an evening of celebration, connection, and entertainment.

This year’s 2025 gala highlighted the incredible mahi of Hato Hone St John on the frontline of medical response and ambulance care in the district, mahi tika ana ngā kaimahi o St John! Te Tiratū acknowledges and celebrates their dedication and tireless work.

The event also provided a space for whānau to share kōrero about health care in Te Awamutu and rural communities. While celebrating available services, attendees spoke openly about the challenges they face in accessing comprehensive hauora support, including high costs, difficulty securing appointments, and care that doesn’t always reflect their unique cultural needs. Some whānau admitted they often avoid check-ups altogether.

A representative from St John, who works in the Emergency Department, shared how these access barriers affect frontline care and highlighted the importance of improving primary care for rural communities. We heard about Kaumātua experiences and the positive impact of Mangatoatoa Health Clinic at Mangatoatoa Marae, noting the critical support provided by Pinnacle and Waikato iwi resources.

The gala also reflected the strong community networks and partnerships supporting hauora across the district. Neighbourhood Watch shared concerns about youth vaping, nangs, meth use, and alcohol, while also noting positive changes such as Kihikihi’s earlier bottle store closing.

Our hardworking Hauora providers emphasised the importance of access for remote and rural whānau and highlighted successful community-led responses, including initiatives from Arahina. The Māori Women’s Welfare League Tainui Branch shared their health programmes delivered in Kihikihi, supporting whānau engagement in wellbeing activities.

Organised by Te Awamutu Sports, Ko Wai Au, and other local groups, the gala was a hugely unifying annual event celebrating the generosity, care, and resilience of whānau and community. Through the kōrero shared at the gala, Te Tiratū reinforces the importance of accessible, culturally responsive health care and the ongoing collaboration needed to ensure whānau in Te Awamutu and surrounding rural areas are supported in their hauora journey.

Te Kūiti Hospital Centenary: Honouring a Taonga of the King Country

From left to right: Kaumātua Ngāti Rora, Kingi Turner, Health Minister Hon. Simeon Brown planting a rākau, Kingi Turner with Lynne Stafford and Charge nurse Tania Te Wano

Te Kūiti Hospital, a treasured taonga of the King Country, has been honoured for 100 years of service to the community.

We were there at the centenary celebration in the weekend at the hospital grounds hosted by Ngāti Rora, brought together staff, whānau to reflect on the hospital’s enduring connection to tangata whenua and the whenua it stands upon.

Ngāti Rora paid tribute to the legacy of those who built and sustained the hospital, from its official opening by Sir Māui Pōmare in 1925 to the dedicated teams who continue to care for the people of the region today.

The hospital sits on land gifted by Rangatira Tanirau Hetet, whose uri attended the centenary to honour the contribution of their tūpuna. Generous support from Tanirau Hetet, who donated 3.5 acres of land, laid the foundation for an enduring partnership between Māori and the Crown to deliver vital health services across the King Country.

For generations, Te Kūiti Hospital has been a lifeline for our whānau, providing emergency, maternity, surgical, and community services across the rohe. Feedback gathered through our Whānau Voice shows that whānau want health care to remain close to home.

Many say that local access to care allows them to stay connected to whānau and whenua, rather than face long and costly travel to Waikato Hospital. A bus service introduced 30 years ago between Taumarunui and Waikato Hospital continues to support whānau who must travel for specialist appointments, a reflection of how community-led solutions have long underpinned rural health care in the region.

For charge nurse Tania Te Wano, who has served Te Kūiti Hospital for three decades, the centenary was deeply personal. Community tributes shared on the Legendary Te Kūiti Facebook page described the hospital’s legacy as one that has produced “iconic surgeons and doctors, medical advancements, births of legends, helicopter transfers, and pandemic responses.”

Health Minister Simeon Brown attended the celebration acknowledging Te Kūiti Hospital as a symbol of perseverance and partnership. He planted a commemorative tree to mark the milestone and recognised the hospital’s ongoing role as one of six rural prototype sites trialling improvements to local health services, including better access to diagnostics, on-call pharmacy support, and digital tools for clinicians.

Te Whatu Ora rural manager Rachel Swain said workforce shortages and aging infrastructure remain challenges for rural hospitals. She highlighted the government’s Rural Health Strategy, which prioritises keeping services close to home, strengthening prevention, and supporting a flexible rural health workforce. Investments in regional training hubs and the new Waikato Medical School aim to grow the next generation of doctors and nurses from within rural communities.

One hundred years on, Te Kūiti Hospital remains more than a place of healing. It stands as a taonga, a testament to partnership between whānau, mana whenua, and health services and a reminder of what can be achieved when care is grounded in place, people, and whakapapa.

Quarterly Report: Evidence, advocacy, & change

Over the past three months, Te Tiratū has continued to lead a powerful wave of Māori advocacy to ensure our people are not sidelined in national health reforms. This quarter has made one thing clear, iwi-led accountability is not just necessary, it is urgent. Our purpose remains unwavering. It is to protect Māori health rights, uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and ensure whānau voices drive the transformation of health services in our rohe.

Our first Monitoring Report, released in June 2025, revealed deep inequities that cannot be ignored. Whānau in our rohe especially in rural communities continue to face poorer outcomes due to cost, distance, cultural inaccessibility and long wait times. Screening participation for breast, cervical and bowel cancer remains below national targets, with many whānau unregistered or unable to access primary care. Critical gaps in data for immunisation, oral health, prostate screening and mental health services prevent true accountability. Delays for cancer treatment, surgery and specialist care are increasing, placing whānau at risk and making equity targets unattainable under the current system design.

Despite these inequities, system-level change is moving in the opposite direction. Our monitoring found that authentic iwi engagement in governance remains unmet, Te Tiriti obligations are being eroded, and Māori providers are still under-resourced and restricted by fragmented commissioning models. The disestablishment of Te Aka Whai Ora and upcoming Pae Ora amendments show a system shifting away from Māori decision-making at the very moment when accountability is most needed.

In this context, Te Tiratū has stepped forward with determination challenging decision-makers, presenting evidence community by community, and putting the lived realities of whānau at the centre of the national conversation. Our advocacy from July to September generated national media coverage, influenced policy discussions with our Position Statement on Rangatahi Mental Health and Diabetes & Podiatry and resulted in direct engagements with Te Whatu Ora, Minister and senior officials. We highlighted the real impacts of system reform on cancer treatment, mental health services and kaumātua care, making it clear that equity cannot be achieved without structural change.

A major milestone this quarter was researching our State of Māori Health Town Report series that will be released over the next four months. For the first time, iwi are independently mapping health access and service quality at a town level across our rohe. We are looking at Taumarunui, Te Kuiti, Thames, Paeroa, Tokoroa, Huntly and beyond. This data with our qualitative Whanau Voice insights is exposing local service gaps, surfacing real-time access barriers and will directly inform decisionmakers.

Today, Te Tiratū represents 121,300 Māori, over a quarter of the Waikato region. This gives us a powerful mandate to negotiate, influence, and protect Māori interests at the highest levels. Our role at the decision-making table is not symbolic; it is strategic, persistent and backed by evidence. We continue to meet regularly with Te Whatu Ora’s Māori leadership and key government officials to ensure that policies are accountable to the people they affect.

Our communications reach has also grown significantly. In July alone, more than 175,000 people engaged with Te Tiratū across Facebook, video storytelling and our new website platform. Māori media and mainstream outlets including RNZ, Stuff, Waatea and the National Business Review have amplified our voice, reinforcing the leadership and credibility of Te Tiratū on health equity.

This quarter has shown that when Māori are informed, united and resourced, we have the power to transform systems from the ground up. Te Tiratū is not waiting for change, we are leading it. The next Quarterly Monitoring Report of Te Whatu Ora will continue to hold the system to account and ensure that inequities, data gaps and access failures are visible and addressed.

Looking ahead, our focus remains on making sure that decisions made in Wellington reflect the realities of our people at home. Whānau voices will continue to drive our reports, shape national direction and guide our advocacy. Te Tiratū exists to ensure that our mokopuna inherit a health system that is equitable, culturally grounded and honours the rights and dignity of Māori for generations to come.

Skin health kōrero at kura draws many in Rāhui Pōkeka

Our Whānau Voice kaimahi attended a community hui at Te Wharekura o Rakaumanga, hosted by Matawhaanui Trust to kōrero about common health challenges affecting tamariki and whānau, with a special focus on skin conditions.

It was a packed and uplifting session, bringing together whānau, nurses, paediatricians, rongoā practitioners and other health professionals who shared their knowledge and practical advice. Among those present were Nurse Practitioner Justina Leaf, CEO of Matawhaanui Trust Joyce Maipi and her whānau, Julia from Sexual Health Waikato, and three paediatricians from the ARROW childhood wheeze trial, Dr Cameron Bennett, Dr Owen Sinclair, and Dr Te Aro Moxon.

The kōrero centred on simple, practical ways to support whānau managing skin issues like eczema and scabies. Dr Owen Sinclair reminded those gathered not to be too hard on themselves, saying the problem is the eczema, not the child. He emphasised that mindset matters, and that parents should not feel blame but instead focus on gentle, consistent care.

Dr Cameron Bennett spoke about the importance of rest, as sleep gives the body time to fight infection, and also shared tips around salt baths, soaked dressings, and managing infections that can complicate skin conditions. Others suggested checking whether soaps or food such as cow’s milk might be contributing to irritation.

For some whānau, cost can be a barrier, and affordable options like adding a teaspoon of Janola to the bath were discussed as simple ways to disinfect the skin when used safely. Parents were also encouraged to make sure that kōhanga or preschools are aware if tamariki have hot or red skin, so early help can be found.

Dr Te Aro Moxon, who works both as a community paediatrician and general physician, spoke about the need to strengthen the link between hospital-based care and the support available in communities. The hui also highlighted the barriers that many whānau face in accessing healthcare, from the cost of travel to Hamilton, to issues of trust, affordability, and feeling heard.

Joyce Maipi, shared a heartfelt story about a young wahine from the community who passed away at just 38 years old from breast cancer that was detected too late. She spoke of her legacy as a reminder to all wāhine to get screened early, noting that the Breast Screening Aotearoa mobile unit is currently parked outside Huntly Woolworths.

Justina Leaf acknowledged that this was the first face-to-face forum held in some time and thanked those who travelled down from Auckland to attend. She shared examples of the manaaki shown by Matawhaanui’s team, from staying on late to help a koro with heart issues, to supporting another with nicotine patches that helped him give up smoking and improve his health. These small but powerful acts of care, she said, are what make the difference for whānau.

Rongoā healers from Te Puna Ora also attended, sharing their mirimiri and natural health knowledge. Julia from Sexual Health Services (formerly Family Planning) spoke about the importance of HPV vaccination and the rising rates of syphilis, encouraging whānau to get checked and treated, especially for the health of unborn pēpi. Rangatahi were also present including nieces and nephews brought along by their aunties and uncles and their participation was warmly acknowledged as a positive sign of intergenerational learning in action.

The hui ended with Ursula from the Electoral Commission encouraging everyone to make their voices count in the upcoming election. For whānau wanting trusted information and support, the KidsHealth website was recommended as a valuable resource for parents, alongside the ARROW study site and the Paediatric Society’s equity commitment page.

It was a powerful and timely reminder that hauora begins at home with aroha, rest, and simple, practical care. By bringing together community voices, health professionals and researchers, gatherings like this help bridge the space between hospitals and homes, between science and rongoā, and between whānau and wellbeing.

Kāwhia whānau lead kōrero on more support

This morning in Kāwhia, a close-knit community of just 378 people, we joined the latest Community Health Forum to kōrero, listen, and offer tautoko. Te Tiratū acknowledges the vital work of Te Whatu Ora kaimahi, who coordinate these hui across the rohe to connect with whānau, share updates, and ensure their voices are heard.

Whānau travelled from across the West Coast Harbours to share their stories, experiences, and priorities for the wellbeing of their whānau and community.

A key priority was funding awareness and support. Whānau highlighted the need for proactive guidance from Te Whatu Ora staff to help them understand and access available funding opportunities. Clear advice, they said, empowers whānau to improve wellbeing, build resilience, and strengthen independence.

Another strong theme was community connection. Whānau spoke about the importance of small, humble events, from karaoke nights to kaumatua creative workshops, which lift spirits and reduce isolation, especially for those living alone.

The forum also highlighted kaumātua support needs. Many kaumātua are struggling with everyday tasks and require consistent, daily support. Whānau spoke about the need for a kaumatua bus, tailored services, and culturally appropriate care to help uphold their dignity and independence.

Transport challenges were another key concern. Funding and reliable transport to Waikato Hospital and nearby towns remain a significant barrier, especially for those requiring regular appointments, specialist care, or after-hours help.

Accessing home help is difficult in isolated areas. Limited carer training and high travel costs make services unaffordable for many whānau. Investment in workforce development and travel support is urgently needed to ensure everyone receives the care they need.

Rangatahi mental health was a serious topic of discussion. Suicide among rangatahi is a concern in isolated communities. Whānau want more clinical expertise, suicide prevention support, and culturally responsive mental health services available close to home.

Primary care workforce shortages were raised as a pressing issue. Dr John Burton, the local GP, has been a lifeline for Kāwhia whānau, but there is uncertainty about future care provision once he retires. Succession planning and investment in rural healthcare are critical to maintaining services.

Whānau also spoke about the need for Disability Allowance awareness. Clear communication and outreach regarding support available through WINZ and ACC will ensure that entitlements are accessed and whānau can receive the help they need.

After-hours care is available through Ka Ora Telecare and 24/7 telehealth services, but these user-pays services can be costly for those without a Community Service Card. Affordable options are needed to ensure whānau can access care at any time.

Public health preparedness was another focus. The Waikato Immunisation and Public Health Teams are coordinating plans in case of measles or other outbreaks. Community awareness and readiness are key to keeping whānau safe.

Finally, whānau highlighted the urgent need for affordable dental services for adults in rural areas, to ensure everyone has access to essential care.

It was clear that the Health Forum shone a light on the power of connection. It reminded everyone that strong kōrero, listening, and care can make a real difference in whānau wellbeing.