Institutions must turn the mirror – that’s where change begins

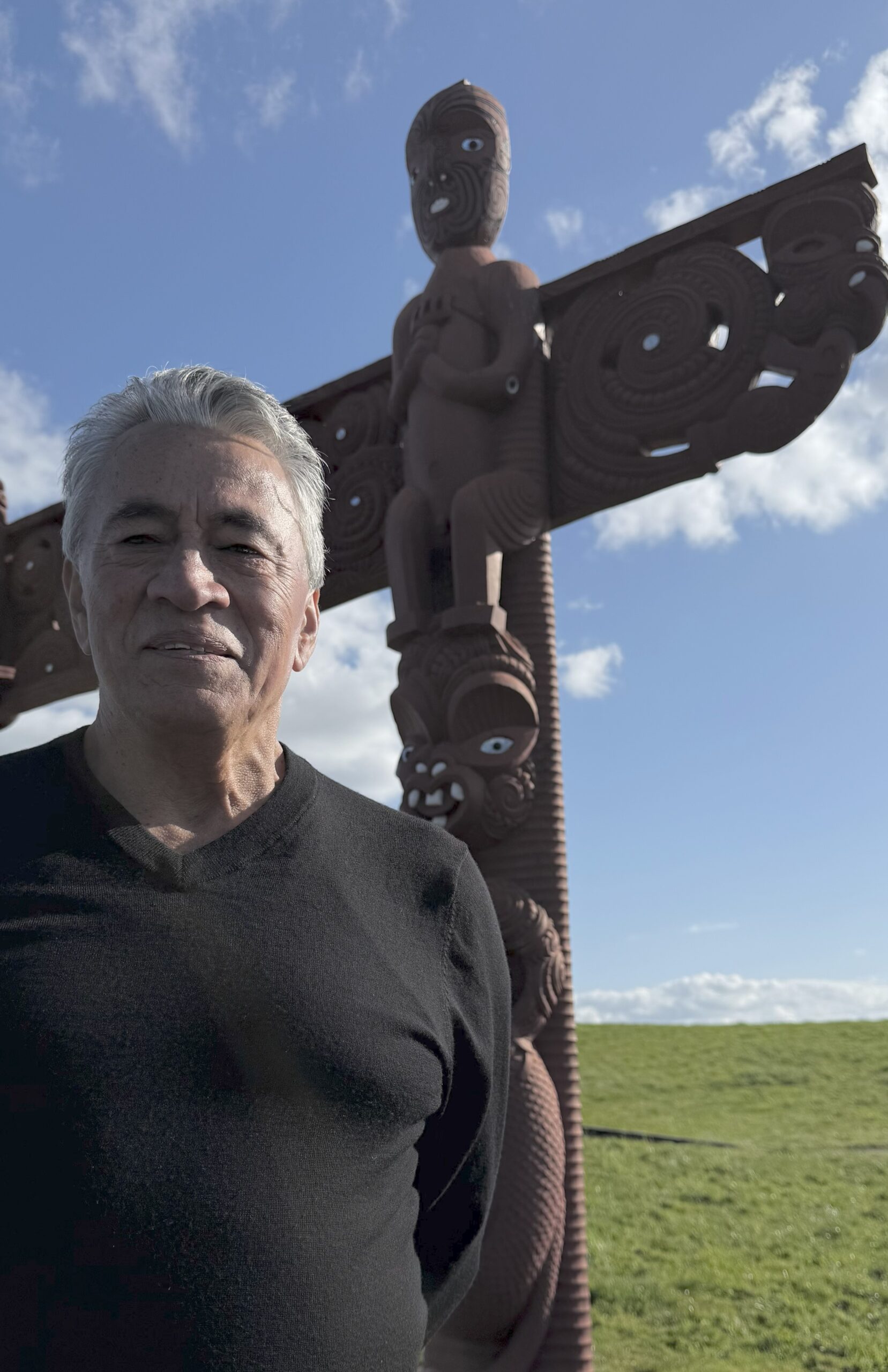

When Glen Tupuhi talks about governance, he doesn’t start with boardrooms or legislation. He starts with whānau.

In a recent radio interview with Ngā Iwi FM, he shared his vision as the new co-chair of Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board. Known across Hauraki and beyond, Ngā Iwi FM is a trusted voice of iwi, hapū, and whānau in our Tainui waka rohe.

With more than 35 years of governance experience, Glen brings a deep understanding of leadership and accountability to his new role. For him, respect within the whānau and marae is the foundation for engaging rangatahi and building the next generation of leaders. His words of advice?

“Cut your teeth at the marae and whānau level. Our whānau are the most brilliant and the most challenging. If you can gain their respect, you’re unbeatable.”

Glen explained how the Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 inquiry shaped the Pae Ora Act, leading to the creation of Iwi Māori Partnership Boards like Te Tiratū, one of the largest across the motu.

“Most of our people are with mainstream services. For years, we’ve asked, if there’s inequity in health delivery to Māori, what is the responsibility of those services? The evidence before the Tribunal was irrefutable,” he said.

The Iwi Māori Partnership Boards under the legislation hold the health system accountable. But Glen says that monitoring role has been weakened with the proposal of the Pae Ora Bill currently before the Health Select Committee.

“We’ve ended up more like an advisory group. Meanwhile, doctors and nurses are powerful bodies in health, so what responsibility have they taken for the legacy of inequity? Everyone needs to step up.”

For Glen, becoming co-chair is a chance to carry the Hauraki voice into health governance trying to embed Māori voices and values into the heart of the system to get it back on the right path.

“On behalf of Hauraki, it’s a privilege to be here. David Taipari and I have always advocated strongly for the Hauraki voice, especially in health. Now we can strengthen that presence at the table,” he said.

He also sees rangatahi as central to the future of iwi leadership.

“I love hearing about rangatahi wānanga because they’re our forerunners. These are the spaces where they can spread their wings and build a great future.”

Glen draws on his years on the Waikato DHB Iwi Māori Council, where he saw the power of institutions taking responsibility for change.

“Instead of blaming Māori for not turning up to appointments, we asked, what is it about the way we deliver health that creates obstacles? It’s about turning the mirror on the institution. That’s where change begins.”

He believes mainstream health services need to adopt the same mindset, with clear measures to ensure equity.

“It’s not about us taking over. It’s about making sure people are delivering well to our whānau. Build equity into KPIs, audit them, and lift performance. That’s how we get real change.”

Call for urgent boost to rural Māori youth mental health services

Brandi Hudson, Te Tumu Whakarae of the Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board, is calling for urgent improvements to mental health services for rangatahi Māori, particularly in rural Waikato.

Speaking in an interview with Waatea News, Hudson says current funding and policy fail to meet the needs of Māori youth, with many rural whānau having to accept under-resourced services as normal. While initiatives like the Pou Wai Project and Hauora Waikato have shown success, they struggle to attract skilled staff and need more support to expand.

“There’s a real need for policy and investment that prioritises rurally based programmes designed and delivered by Māori, for Māori,” Hudson says, stressing that one-size-fits-all approaches won’t address the unique challenges of rural communities.

Glen Tupuhi appointed to Te Tiratū role

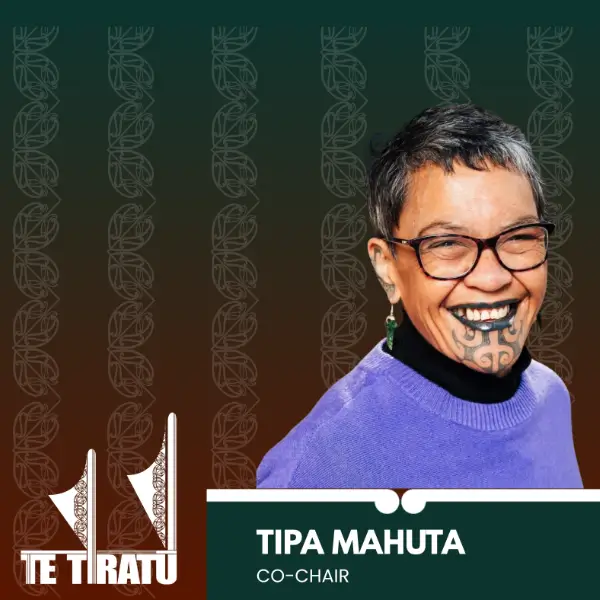

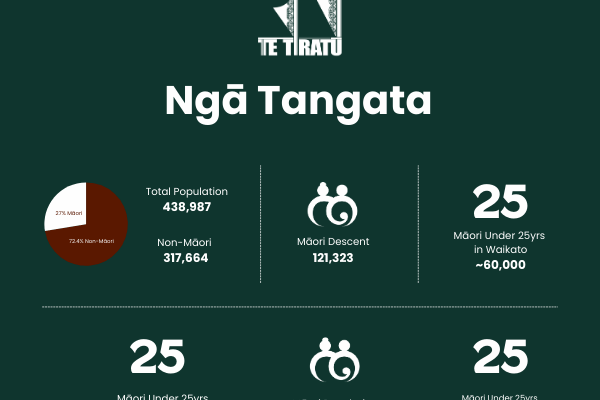

The National Business Review (NBR) reports that Glen Tupuhi has been named co-chair of Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board, joining Tipa Mahuta and succeeding Hagen Tautari. Te Tiratū, one of 15 boards established under the Pae Ora Act, represents around 121,000 Māori whānau across the Tainui waka region and ensures Māori perspectives shape local health services.

Tupuhi brings over 30 years of experience in Māori development across health, education, and justice, with leadership roles at Oranga Tamariki, Health Waikato, Hauora Waikato, Corrections, and Te Rūnanga o Kirikiriroa. He also serves on multiple boards, including Winton Land, Te Korowai Hauora o Hauraki, and the Hauraki PHO, and has led key economic and development initiatives in North Waikato.

Affiliating with multiple iwi across Waikato and Tāmaki Makaurau, Tupuhi’s appointment underscores Te Tiratū’s commitment to strong, culturally informed governance. Co-chair Tipa Mahuta welcomed him, thanking Tautari for his service and expressing confidence in Tupuhi’s leadership.

Rangatahi Māori mental health in rural Waikato is in crisis

MEDIA STATEMENT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Tuesday 23 September 2025, 4:00 PM

2 minutes to Read

Despite the government’s ambitious July 2024 mental health and addiction targets, rangatahi Māori in rural Waikato are falling through the cracks. Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand data with evidence from Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board and local whānau voices shows that services are under-resourced, overstretched, and failing to meet the standards set by the government to monitor of health system performance by the Ministry.

National government targets include:

- Faster access to services: 80% of individuals to reach primary mental health and addiction services within one week, and mental health specialist services within three weeks.

- Emergency department efficiency: 95% of mental health-related ED presentations admitted, discharged, or transferred within six hours.

- Workforce development: Train 500 new mental health professionals annually.

- Prevention and early intervention: Allocate 25% of mental health funding to prevention.

Reality on the ground in rural Waikato:

- Over 200 tamariki/rangatahi have open referrals, with waitlists rising steadily since 2023 including 10 per month waiting for ADHD assessments and 21 for other mental health services.

- Frequent crises: Average of 10 crisis contact days per month, with 79 under-25s admitted to Henry Rongomai Bennett Centre since 2021 (average stay 14 days).

- Rural workforce gaps: Schools and providers rely on Police, St John, and Women’s Refuge to manage crises, far beyond their scope. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and counsellors are largely unavailable locally.

- Prevention funding gaps: Iwi- and whānau-led programmes like Hauora Waikato, Te Awhi Whānau, and Puāwai Project are underfunded despite proven success in building resilience and wellbeing.

“Our rangatahi are simply falling through the cracks,” says Brandi Hudson, Te Tumu Whakarae of Te Tiratū IMPB.

“The government has set clear targets, yet in rural Māori communities we are seeing long waits, repeated crises, and preventable hospitalisations. Immediate, targeted, and culturally grounded investment is not optional, it is urgent. I will be raising these issues directly with Minister Doocey when he visits Te Kūiti on Wednesday as part of his Rural Roadshow.”

Te Tiratū is calling on the government to prioritise early intervention and prevention for rural Māori youth, expand workforce capacity in King Country and other rural areas, fully resource iwi- and whānau-led programmes that are already proving effective, and ensure funding reaches the communities most at risk, not just metropolitan centres.

Without urgent action, the mental health crisis among rangatahi Māori will worsen, with devastating long-term consequences for whānau, communities, and the health system.

The Te Tiratū Iwi Maori Partnership Board represents the interests of 121,000 whānau Māori in the Tainui waka rohe and encompasses iwi from Waikato, Pare Hauraki, Raukawa, Te Nehenehenui (Maniapoto), Ngāti Hāua (Taumarunui), and Te Rūnanga o Kirikiriroa (Mātāwaka).

Minister Doocey will be at the Les Munro Centre in Te Kūiti for the Rural Roadshow from 12pm-1.30pm tomorrow.

Our strong warning that rangatahi Māori in rural Waikato are facing a mental health crisis.

Read the statistics Te Tiratū has gathered specifically for our Tainui waka rohe.

Glen Tupuhi appointed Co-Chair of Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board

MEDIA STATEMENT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Tuesday 23 September 2025, 9:00 AM

2 minutes to Read

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board (IMPB) representing 121,000 whānau across the Tainui waka region and one of the largest of the 15 Iwi Māori Partnership Boards established under the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act is pleased to announce the appointment of Glen Tupuhi as Co-Chair.

He replaces Hagen Tautari, who has provided strong leadership and guidance governing to date. Tipa Mahuta, current Co-Chair, expressed her gratitude for Hagen’s service.

“On behalf of Te Tiratū IMPB, we sincerely thank Hagen Tautari for his dedication and commitment to the kaupapa, our whānau, and the wider Māori community. We are delighted to acknowledge Glen Tupuhi as our new Co-Chair and look forward to his leadership in guiding the Board forward,” she said.

From his time as chair of the Murihiku Māori Health Committee of the Southland Area Health Board in the mid 1980’s Glen brings over 35 years of governance experience across the Māori development, health, education, and justice sectors. His extensive background includes Iwi Hapuu Marae leadership roles as well as managerial roles in Oranga Tamariki, Corrections, Health Waikato, Hauora Waikato, and Te Rūnanga o Kirikiriroa. He has also served on the Auckland Council Independent Māori Statutory Board and the Māori Economic Development Panel.

Currently, he holds multiple governance roles, including:

- Independent Director, Winton Lands Ltd

- Board Member, Te Korowai Hauora o Hauraki and the Hauraki PHO

- Chair, Hauraki Localities Alliance

- Until recently Trustee of Ecoquest Education Foundation PTE and chair, Ngaa Muka Development Trust

A seasoned leader in integrating cultural perspectives with commercial decision-making, as chair of Ngaa Muka Glen has successfully guided iwi partnerships in projects across North Waikato such as Cobb Vantress chicken breeding plant, Lakeside development in Te Kauwhata and the initial establishment of the Sleepyhead Estate at Ohinewai, a $1.2 billion mixed-use industrial and residential development in North Waikato.

Glen’s iwi affiliations include Ngāti Pāoa ki Waiheke, Tamaki Makaurau, Hauraki, Waikato, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Naho o Waikato, Ngāti Rangimahora, and Ngāti Apakura. His leadership philosophy emphasizes collaboration, strategic oversight, and creating sustainable opportunities for whānau and communities.

In addition to his professional and governance work, Glen continues to support whānau trusts and philanthropic initiatives, including the Whakatupu Aotearoa Foundation, fostering system-level change for communities and the environment in Aotearoa.

His appointment reflects Te Tiratū IMPB’s ongoing commitment to strong, culturally-informed governance, and the Board looks forward to the expertise, guidance, and leadership he will bring in advancing the aspirations of iwi and whānau across the region.

The Board encompasses iwi from:

- Waikato

- Pare Hauraki

- Raukawa

- Te Nehenehenui (Maniapoto)

- Ngāti Hāua (Taumarunui)

- Te Rūnanga o Kirikiriroa (Mātāwaka)

Proposed Pae Ora reforms lack evidence & crown’s Te Tiriti partnership with iwi non-negotiable

MEDIA STATEMENT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Friday 1 September 2025, 8:00 AM

2 minutes to Read

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board (IMPB), representing over 121,000 Māori across the greater Waikato region, will present its submission opposing proposed changes to the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act on Wednesday 3 September at 1.00pm.

One of fifteen Iwi-Māori Partnership Boards across Aotearoa, Te Tiratū stands united against proposed Pae Ora changes that would strip Te Tiriti protections, curb Māori decision-making, and deepen health inequities.

The Board warns that altering the roles and functions of IMPBs under Section 30 would undermine the Government’s commitments to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, equity, and meaningful Māori participation in health decision-making.

“Our leadership, knowledge, and influence are already delivering tangible results for whānau Māori,” said Co- Chair Tipa Mahuta. “The proposed reforms are not supported by evidence or Māori health data and risk reversing progress on improving outcomes for our communities.”

Te Tiratū highlights that IMPBs play a critical role in local and regional health planning, monitoring, and prioritisation, ensuring Māori voices and mātauranga Māori are central to decisions. Through initiatives such as the Community Health Plan and ongoing monitoring reports, IMPBs provide actionable insights to Health NZ and other agencies to drive better outcomes and stronger returns on taxpayer investment.

The Board points to decades of Māori-led success in health services, including the rapid and effective COVID-19 response, demonstrating that locally-led, iwi-driven solutions outperform traditional government approaches. Yet, Māori health inequities persist, with ongoing gaps in cancer screening, access to primary care, and chronic disease management. IMPBs are uniquely positioned to be the circuit-breaker to these long-standing disparities.

Te Tiratū also notes that the Government’s broader economic goals, including the “Going for Growth” Māori economic strategy, depend on healthy, supported whānau. IMPBs, if empowered, can drive innovation, workforce development, and local investment in health infrastructure, further supporting Māori economic growth.

“The Crown’s duty to partner with iwi under Te Tiriti o Waitangi is non-negotiable,” said Mahuta. “IMPBs must retain their legislated functions. Removing or diminishing our role risks repeating decades of systemic failure and wasted taxpayer resources.”

Te Tiratū urges the Minister of Health and Government to uphold Section 30 of the Pae Ora Act, ensuring IMPBs continue to lead, influence, and transform Māori health outcomes.

Iwi Māori Partnership Boards concerned their role minimised under Pae Ora Act changes

Photo: Te Manawa Taki IMPB collective member, Te Taura Ora o Waiariki Chair Hingatu Thompson

RNZ reports about the unified stance of all 15 Iwi Māori Partnership Boards (IMPBs) coming together in Taranaki for a two-day National Hui, expressing concern that proposed changes to the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act would diminish their role in New Zealand’s health system. Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board shares this opposition, highlighting that local, iwi-led decision-making and accountability are essential to improving Māori health outcomes.

Leaders at the hui said that the proposed amendments risk silencing Māori voices, removing direct iwi oversight, and limiting the ability to deliver whānau-centred health solutions. IMPBs were established under Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles to ensure Māori engagement with the Crown, guide local health strategies, and address systemic inequities such as lower life expectancy and poorer outcomes for Māori.

The hui highlighted concerns over four key areas: maintaining Te Tiriti protections in legislation, ensuring the Hauora Māori Advisory Committee is accountable to iwi, retaining a Māori health strategy, and preserving the critical role of IMPBs in regional health planning. Te Tiratū reinforced that strong local partnerships and culturally responsive approaches are vital to achieving equity and improving Māori health.

Iwi Māori partnership boards unite to oppose changes to health legislation

Photo: Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board Co-chair Hagen Tautari

Iwi Māori Partnership Boards (IMPBs) from across Aotearoa are standing together to oppose proposed amendments to the Pae Ora Act, raising concerns that the changes would weaken their statutory role and reduce Māori oversight in the health system. The fifteen boards, representing over 900,000 Māori, are meeting in New Plymouth for the first time since the Bill’s first reading to build a unified national voice, safeguard local accountability, and ensure health services remain responsive to whānau needs. The hui and the boards’ stance have been covered by 1News/Te Karere highlighting the nationwide concern that these changes could undermine decades of partnership work and progress in Māori health equity.

Iwi Māori partnership boards unite to oppose changes to health legislation

The stance of Te Tiratū as part of a national alliance of 15 IMPBs united in opposition to proposed amendments to the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act has been covered by Te Karere, highlighting the national conversation around Māori leadership in health.

The national collective warns that the changes would weaken Te Tiriti-based partnerships and threaten Māori health equity. The National IMPB Hui in New Plymouth attracted representatives from 82 iwi, representing the interests of over 900,000 Māori. Rangatahi attendees highlighted the links between hauora, whakapapa, and whenua, reinforcing the need for health solutions that integrate ancestral knowledge with modern systems.

A Te Tiratū spokesperson emphasised that IMPBs must remain active partners in shaping local and regional health strategies, including targeted Māori equity actions, and that any amendments undermining Te Tiriti principles must be opposed.

Our nationwide stand with all IMPBs against proposed Pae Ora Bill changes

Photo: Board member Maxine Ketu and e Tiratū Tumu Whakarae, Brandi Hudson attend the National IMPB Hui in New Plymouth

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board (IMPB), as part of a national alliance of 15 IMPBs, opposes the proposed amendments to the Pae Ora Act, warning that the changes would weaken Te Tiriti-based partnerships and undermine progress in Māori health equity.

At a recent National IMPB Hui in New Plymouth, 15 IMPBs representing 914,400 Māori from 82 iwi aligned in opposition to the Bill. The discussions highlighted the critical importance of maintaining partnerships that are rooted in trust, respect, and intergenerational thinking, ensuring solutions are anchored in mātauranga Māori and the realities of whānau.

The hui included rangatahi voices emphasising the deep connections between hauora, whakapapa, and whenua. Their presentations stressed the need for health approaches that integrate ancestral knowledge with modern, data-driven health systems. This interweaving of the old and the new highlighted the value of locally led solutions that resonate with whānau and communities.

Te Tiratū IMPB asserts that the proposed changes would remove direct iwi accountability, replacing kanohi ki te kanohi relationships with a centralised, Minister-appointed process. This approach risks tokenistic consultation rather than genuine Māori leadership, and threatens the hard-won equity gains achieved by IMPBs over the past decade.

The Board’s position is clear: local accountability through IMPBs must remain, regional advice to Te Whatu Ora must be strengthened, and health strategies must include specific Māori equity actions. Any amendments that weaken or replace Te Tiriti principles are opposed.

Te Tiratū IMPB submitted its formal response to the Health Committee on 18 August 2025, supporting a unified IMPB call to:

- Retain HMAC accountability to iwi through IMPBs

- Strengthen IMPB roles for local and regional advice to Te Whatu Ora

- Develop health strategies with targeted Māori equity actions

- Oppose amendments that undermine Te Tiriti principles

Our Board emphasises that this is about safeguarding the right to lead local solutions for Māori communities. Analysis shows the proposed changes are unlikely to improve Māori health outcomes, reinforcing the need to maintain systems that are already showing results.

Te Tiratū IMPB remains committed to advocating for whānau-centred health solutions and ensuring Māori voices remain central in shaping Aotearoa’s health system.