What whaanau told us at Tainui Hui-aa-Tau

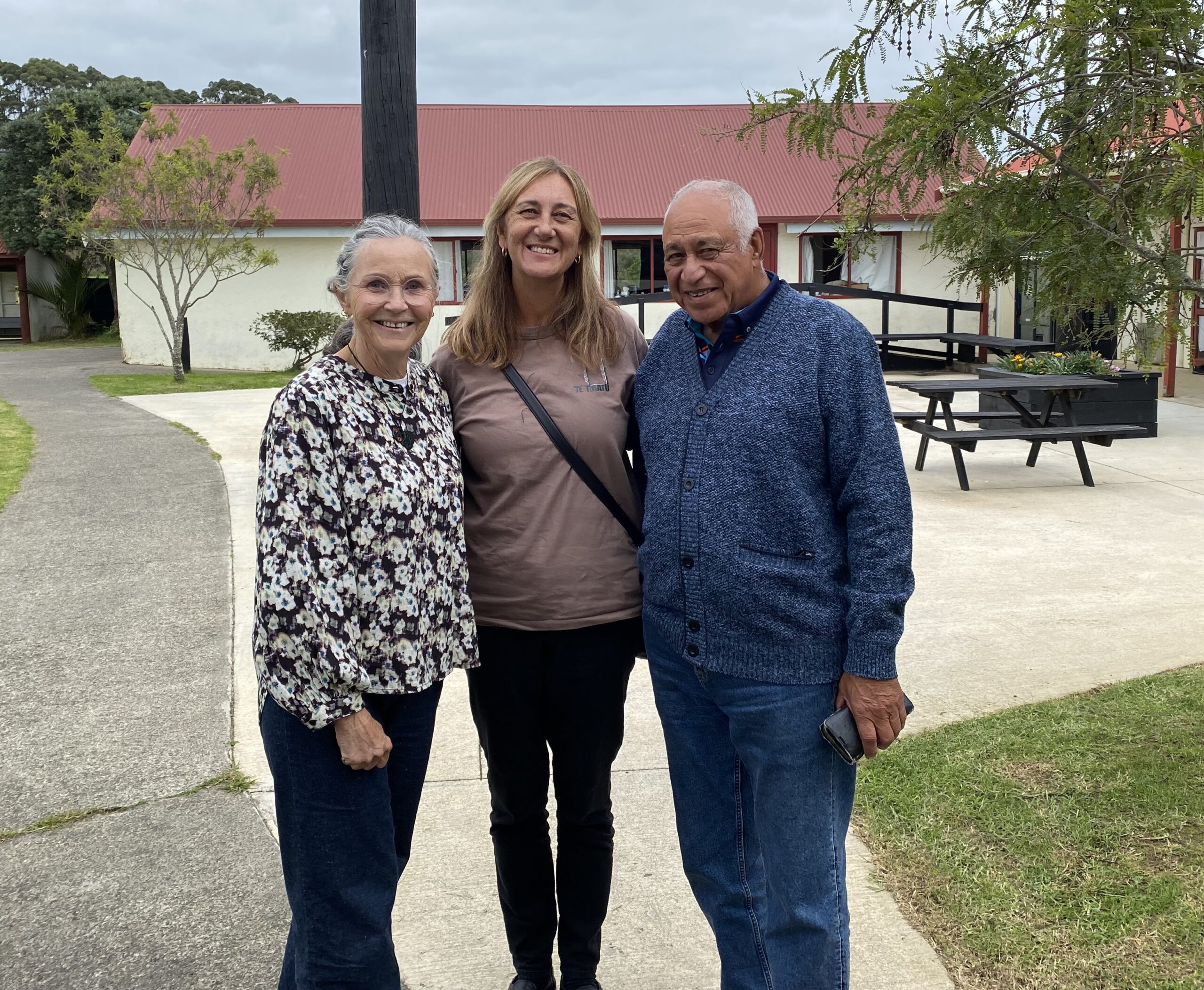

Photo: Whaaea Audrey Wildermott, Ngaati Koroki Kahukura with Whaanau Voice kaimahi

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board was honoured to attend Tainui Hui-aa-Tau 2025, hosted by Tainui iwi walking in the steps of their visionary Koiora strategy. This aspirational kaupapa brought together thousands of uri and providers across the motu to connect, share, and strengthen collective oranga.

We were there by invitation to support Whaanau Voice and deepen our understanding of how the Koiora Collective and Te Tiratū fit within the wider ecosystem of Māori health and wellbeing. While our original focus was on promoting our Oranga Survey the day quickly turned into something more — a space for heartfelt koorero and deep listening.

What we heard was despite government targets focused on faster cancer treatment, shorter ED stays, improved immunisation, and reduced wait times for specialist and elective care, whaanau at Tainui Hu-a-Tau described a system that remains slow, hard to access, is culturally disconnected, and difficult to navigate — especially for whaanau seeking kaupapa Maaori services and timely, affordable care.

Whaanau Voice Leads the Way

Our space at Hui-aa-Tau was a hive of activity, filled with whānau keen to share their experiences and insights about accessing healthcare. Many whaanau wanted to koorero at length, reflecting a widespread desire to be heard. Primary care was a consistent topic. Whānau spoke about long GP wait times, often up to four weeks, difficulty enrolling at kaupapa Maaori clinics due to capped rolls, and the frustration of not being able to see the same doctor for continuity of care. Many whaanau living rurally shared feelings of isolation from healthcare, relying on transport support from whaanau, iwi or local services. For those who could afford it, urgent care was preferred over long waits at emergency departments, but even this came with financial strain.

The Strain of Financial Pressure

Cost was a major barrier. Whaanau shared stories of having to choose between kai and seeing a doctor. Prescriptions added another burden. Even if a whaanau member managed to secure an appointment, the costs didn’t end there. Some spoke of giving up altogether — delaying care or avoiding it until it became urgent. Many whaanau weren’t enrolled with a GP at all. Some had been trying to enrol with kaupapa Maaori services but were turned away due to capacity limits. Several questioned why non-Maaori were enrolled in Maaori-specific services when they, as tangata whenua, were being declined. There was deep mamae in these koorero, and a desire for a fairer, more culturally grounded system.

The Challenge of Health Literacy for Kaumatua

Kaumatua shared personal journeys of navigating health conditions and the system without proper explanations or support. One kaumatua described an 18-month journey to get assistance to help manage his diabetes to get it under control which is a long time to be mauiui. Others expressed confusion around medication or what services were available to them. Many didn’t know where to go or how to ask for help, and several mentioned feeling whakamaa about not understanding their conditions. The language barrier was another big one, where whaanau are not able to understand a lot of different accents by non-Maaori health practitioners, they feel there is a lack of cultural safety too. For kaumatua living rurally, transport remains another major barrier. Many said that it was much easier for them to go to their local marae that was close. Many rely on once-a-week iwi transport or local hauora hubs that have now been scaled back due to funding cuts. In some areas, services that once operated five days a week now open for just one — creating high demand and limiting access.

Mental Health in Crisis

Mental health was another area of concern. Many who spoke were supporting a sibling, cousin or other whaanau member. The main issue raised was the lack of support available before a person reaches crisis or hospitalisation. Henry Bennett Centre came up repeatedly — described as difficult to deal with, lacking cultural safety, and disconnected from whaanau. Whaanau described not being informed about loved ones’ care, feeling shut out of the process, and being left to advocate for their whaanau without support.

There was a strong call for mental health services that are proactive, culturally safe, and easy to navigate. Many felt stuck trying to get help for their whaanau and repeatedly faced barriers in the process.

The Hidden Gaps in Women’s Health

A number of wahine raised concerns about the lack of accessible information around menopause. They described debilitating symptoms and feeling unsupported or dismissed. Some were surprised to learn just how little was publicly available in terms of education and care. The koorero made it clear that more kaupapa Maaori women’s health services are needed — both in delivery and in design.

Hearing Loss, Delayed Care and Advocacy

Hearing support was another unexpected but prominent theme. Many whaanau attending the hui wore hearing aids, yet no hearing-focused service was present. One kaumatua, a veteran of the New Zealand Army, shared that it took years to realise the extent of his hearing loss. Another wahine described the two-year process of trying to get care for her daughter — eventually only made possible with the help of a Maaori advocate. For these whaanau, accessing support required determination, energy, and navigating complex systems. Funding options, eligibility, and appointment access created further layers of stress. Even for tamariki, care was delayed — sometimes for years. While support grants like the kaumatua hearing aid fund exist, awareness and accessibility remain major gaps.

The Need for Rongoaa and Kaupapa Maaori Options

Throughout the day, whaanau called for more access to mirimiri and rongoaa Maaori. There was a hunger for services that reflect maatauranga Māori and are grounded in whakapapa and whaanau values. One whaanau member, supporting a younger relative who had experienced a stroke, spoke of the lack of Maaori-led recovery options. Others expressed interest in alternatives to mainstream medication but didn’t know where to start. The desire for Maaori-led, whaanau-centric, culturally affirming care was one of the strongest themes to emerge. It aligns closely with the aspirations of Tainui’s Koiora strategy and the values Te Tiratū holds as we walk alongside whaanau and providers.

A Call to Honour Whaanau Voice in System Change

Tainui Hu-aa-Tau 2025 was more than an event — it was a collective pulse check on how the health system is serving our people. Whaanau were open, honest, and generous with their koorero. Their insights paint a clear picture of a system that needs to evolve, one that genuinely centres Whaanau Voice, upholds Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and recognises hauora as a right, not a privilege. We are committed to carrying these voices forward — into our planning, our advocacy, and our partnership with Te Whatu Ora. We also mihi to Tainui iwi for their bold leadership and vision, and for the opportunity to stand together in kaupapa Maaori-led transformation. Te Tiratū will continue to listen and act — because when whaanau speak, the system must listen and respond.

Rangatahi straight-up truths about hauora

Photo: Rangatahi Mokoia Hamiora-Houghton, the Kaitautoko/Kaitiaki of students from Rototuna High School attending the Kapa Haka and a Taiohi forum organised at Claudelands by Te Puna Wananga o Wairere.

Our rangatahi aren’t just open to kōrero—they’re confident, articulate and have important whakaaro that health leaders must listen too. In June, 96 chose to share their views through Whānau Voice surveys gathered both online and face-to-face. Combined with broader findings from our Community Health Plan, first Monitoring Report, and engagement activities between March and June, their voices offer powerful and direct insights into the health and wellbeing issues they care about most.

While many rangatahi were unfamiliar with some medical terms—particularly questions around the HPV vaccine—they showed curiosity and deep interest in learning more once questions were explained in plain language. What followed was a series of straight-up reflections that reveal the aspirations and challenges our young people face every day.

Mental health emerged as the number one concern. A third of all respondents saying they want more support and information in this space. Sexual health was another key area, especially among rangatahi worried about teen pregnancy and gaps in knowledge. Nutrition, the rising cost of healthy food, the dangers of vaping, and curiosity about rongoā Māori also featured strongly.

Here’s some of what they said:

- “Mental health & the dangers of vaping.”

- “As there’s so much teens who are hapū I feel like there needs to be more health info regarding sexual health and pregnancy.”

- “Nutrition info, particularly considering veggies and fruit are so expensive.”

- “More info about mirimiri in general would be awesome.”

What would help rangatahi stop – or not start – vaping? A lot of rangatahi told us they had tried vaping or were still vaping, even those as young as 12–17. They’re worried about how easy it is to access vapes, and many felt there should be tighter rules – like bans, stricter age checks, less advertising and more support.

Some of their whakaaro:

- “Ban vaping”

- “More restrictions, not advertising, and explaining the danger”

- “Need ID to purchase. There are places you don’t need it”

- “Give out methanol mints to encourage them to stop vaping”

Almost one in four said vaping should be banned or more tightly restricted. They also pointed to peer pressure as a key driver, and many said more mental health support and access to alternative activities—like sport, music, or creative outlets—would make a real difference.

“It’s the popularity of it, if mates do it others will too,” one rangatahi said.

Do rangatahi know about the HPV vaccine? Just over half had heard of the HPV (Human Papilloma Virus) vaccine. But nearly a third hadn’t, and some weren’t sure. It highlighted a mixed picture around the HPV vaccine. A significant number weren’t sure if they’d even been offered the vaccine at all, showing that school-based communication and consent processes may need strengthening. Even among those who had the vaccine, many still lacked clear understanding about what the vaccine is, why it’s important, or what it does in their bodies. This shows there’s still a big gap in the way health info is shared with our rangatahi – and it’s something we can work together to improve.

This kōrero with rangatahi reminds us that they are thoughtful, brave and full of ideas. When we take time to kōrero properly, they show up and are ready to lead, if we’re willing to listen. Their insights call for us—whānau, schools, health providers, and communities—to create safe space for deeper conversations and to ensure our health systems are reaching them with the right tools, messages, and manaakitanga. Our rangatahi have the answers. It’s time we act on them.

What’s really happening with cancer screening our rohe

Cancer impacts countless whānau across Waikato—and feedback from 23 whānau within the Tainui waka region, together with broader insights from our Community Health Plan, initial Monitoring Report, and engagement efforts from March to June, is revealing what’s effective, what’s falling short, and where services need to improve.

Our first Monitoring Report, released this month, shows that breast screening rates for wāhine Māori in Waikato continue to lag behind. Currently, just 54.5% of our wāhine are up to date with screening—7% lower than the national rate for non-Māori (64.6%). While there has been a small improvement of 1.1% since the last quarter, the pace of change remains too slow to close the equity gap.[1]

Most surveyed by our Whānau Voice team (nearly 74%) told us they regularly take part in cancer screening, particularly breast and cervical checks. Many said this is driven by personal or whānau experience of cancer. One participant shared: “My mum had cancer… I made self-referrals. I know how important it is to catch it early.”

But behind those statistics lies a more complex picture. Screening isn’t always comfortable. Over half of respondents said the process left them feeling whakamā, exposed, or in pain. Several described experiences that were rushed or poorly explained—leaving them uncertain, anxious, or unlikely to return. One woman shared: “Didn’t want to go back after last time—felt exposed.” Another added: “It was painful and no one explained anything.”

This discomfort was often made worse by a lack of cultural safety. Māori participants talked about mispronounced names, feeling spoken over, or being asked sensitive questions without privacy. “The lady at reception was white and made no effort to pronounce my Māori name,” said one. Others spoke of rushed appointments and the feeling that their experience wasn’t respected or mana-enhancing.

Not everyone receives timely results, either. Some whānau said they had to chase clinics for updates, while others described waiting months for treatment—even when a diagnosis had already been made. One respondent noted: “We waited 3–4 months, even with private insurance. Treatment took 6–9 months. Too long.”

The good news? Whānau know what would help.

They asked for more Māori doctors and support workers, better access to information, and culturally grounded care that includes warm, respectful service and more whānau-friendly settings—like marae, mobile clinics, or iwi spaces. Many called for free screening for kaumātua, flexible appointment times, and reminders by text or email, noting that these are not offered consistently.

Suggestions were practical and clear:

- “More Māori health professionals, please.”

- “Better-informed and pre-screening promotion.”

- “Use marae and iwi groups to get the message out.”

- “Have a Māori support person due to the medical language.”

A little over half of those surveyed also had a whānau member diagnosed with cancer in the last three years, and nearly half of them said they did not receive enough information about the treatment journey or support services.

There’s a clear call here—not just for more education and outreach, but for services that genuinely listen, respond, and hold space for whānau with care. As one whānau put it: “We need more manaaki-focused care. It makes all the difference.”

This kōrero reinforces the need for screening services that don’t just invite people in but hold them with dignity, understanding, and culturally safe support. Because early detection saves lives—but only if our people feel safe enough to walk through the door.

[1] Pg 13 Source: https://tetiratu.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2025-Te-Tiratu-IMPB-Monitoring-Report-to-March-2025.pdf

GP door closed for many: Whānau speak out

Photo: Kuia providing feedback at a recent Taumarunui Hapori Hauora Day

“We waited eight hours, and no one even told us how long it would be.”

This is the reality for many Māori whānau in the Waikato region, as shown in the latest Whānau Voice quarterly results that reveals the deep cracks in our primary care system.

These insights are drawn from a snapshot survey completed by 88 participants, alongside wider data gathered through our Community Health Plan, first Monitoring Report and engagement activities held between March and June. Their voices paint a clear picture judging by the indicative results, that our local health system is under immense pressure, and it’s pushing whānau to breaking point.

Despite more than 90% of respondents being enrolled with a regular GP, nearly 40% said they were unable to get an urgent appointment when they needed one. For many, the GP door feels effectively closed—whether due to fully booked clinics, high costs, or services being unavailable altogether.

In the first Health System Monitoring Report by Te Tiratū released this month, we note that key data from Te Whatu Ora is still missing. This includes:

- GP enrolment figures compared to the population (Māori vs non-Māori by age)

- Māori utilisation of GP services over the past 12, 24, and 36 months

- Māori utilisation by type of service (in-clinic vs virtual)

This lack of data limits our ability to assess equity in access and use of primary care services for Māori.[1]

So, in these moments of urgency, whānau are being forced to turn to urgent care clinics or hospital emergency departments for care that should be delivered by a GP. Nearly three-quarters of those surveyed said they had gone to A&E when they couldn’t get a GP appointment.

Of those, 29 percent reported waiting six to eight hours. Nine percent said they waited more than ten hours. Most waited without receiving any updates or basic information—86 percent received no health information during their wait, and 84 percent weren’t told how long the wait would be.

Adding to the strain, more than half of respondents said cost had stopped them or their whānau from getting care. This was particularly true for those in remote or rural areas like Tokoroa, Waharoa, and Huntly, where choices are limited and even getting to a clinic can be a challenge.

Some whānau reported being unable to enrol with a GP because no clinics were accepting new patients, or they lacked the required ID. These are not isolated stories; they reflect systemic barriers that need urgent attention.

What is Working?

Not all findings were bleak. Most people reported being able to get planned appointments when needed, and those who used telehealth services found them useful—90 percent said the advice met their needs.

Enrolment in a regular general practice remains high, which shows that there is a foundation to build from. But trust and consistency remain issues, with more than half saying they don’t get to see the same doctor each time.

This survey doesn’t just reveal long wait times or stretched services—it highlights the emotional weight of a system that too often leaves Māori whānau out of reach. It tells a story of people navigating closed doors, cost barriers, and uncertainty, just to access the care they deserve.

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board is using this data to advocate for urgent investment in services that are responsive, affordable, and culturally safe. Because no one should have to wait ten hours in an emergency room for care that should have been delivered in a clinic—least of all our tamariki and kaumātua.

[1] Pg 4 Source: https://tetiratu.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2025-Te-Tiratu-IMPB-Monitoring-Report-to-March-2025.pdf

Rangatahi real talk at the Kapa Haka regionals

Photo: Rangatahi with Ngatini Torea and Raven Torea, Whānau Voice kaimahi

“We’re aware. We just need more support.”

That was the clear message from rangatahi and whānau who engaged with our Whānau Voice kaimahi at the inaugural Te Mokotini ki Tainui and Tainui Secondary School Kapa Haka regionals over the weekend. Alongside thousands gathered to celebrate te ao Māori, haka excellence, and hāpori, our Te Tiratū stand was part of a ‘Hauora Hub’ inside the doors of Claudelands Event Centre. The whare was humming with conversation — and concern. From rangatahi to kaumātua, whānau shared openly about their health journeys, what’s working, and what’s failing them.

What Our Rangatahi Are Saying

Across two days, rangatahi spoke frankly about what they’re facing. They’re switched on and vocal about the lack of mental health and sexual health education in schools — especially around hauora hinengaro. Many shared they learn more from social media than from the classroom. They know mental distress is a problem among their peers but feel unsupported by the current system. They want more—more kōrero, more guidance, and more honest talk in safe spaces. One rangatahi said it best: “We talk about it on TikTok, but not in class. That’s not right.”

Vaping: From “Cool” to “Can’t Stop”

We were alarmed by how widespread vaping is among rangatahi, particularly those aged 12 to 17. Nearly all told us they had easy access — either through shops not checking ID or older siblings buying on their behalf. What began as something “cool” quickly became something they couldn’t stop. Many now feel addicted. They want to quit, but said it’s hard — and support is scarce.

Their message was clear: restrictions aren’t enough. They believe a total ban is the only way to truly protect rangatahi. Importantly, they also called for earlier education, aimed at tamariki aged 10–12, before peer pressure kicks in and the dreaded addiction cycle begins.

Vaccination? Yes. Understanding It? Not So Much.

While most rangatahi had received their HPV vaccination at school, nearly none knew what it was for. One said: “I just signed the form. I didn’t even know what it was.”

This shows a huge gap in informed consent and health literacy. Our tamariki and rangatahi deserve to know what’s going into their tinana and why.

Primary Care: Cost, Wait Times & Whānau Avoiding Help

Whānau told us loud and clear: “If it’s not for the tamariki, we just don’t go.” The reasons are simple — long wait times and unaffordable costs. Standard GP visits range from $60 to $80, and after-hours care can be as high as $180. Many are turning to emergency departments by default, not because it’s ideal, but because it’s faster and more accessible. For some, the choice between paying rent or seeing a doctor isn’t really a choice — it’s about survival. While telehealth works for a few, unclear pricing has left others feeling misled — one whānau member was shocked when their father’s online consult cost more than an in-person visit.

Cancer Screening: Awareness Growing, But Gaps Remain

Many whānau had been screened for breast, cervical, or bowel cancer, but few had completed all three — and most had to initiate the process themselves, with little guidance from GPs or nurses. A registered nurse told us that while reminders appear in patient files, many health professionals simply overlook them. For wāhine, the screening experience was often described as cold and clinical, lacking cultural safety, with many feeling whakamā — exposed, undignified, and unlikely to return. There was positive feedback too, particularly around cervical screening reminders, which were clear and helpful, and the fast, reassuring turnaround times for breast screening results. However, follow-up care was inconsistent, and whānau made it clear they want more community-based education and engagement — they want to understand what to expect, why it matters, and how to access care before it becomes urgent.

Thank you For Your Truths

We’re deeply grateful to every whānau member and rangatahi who stopped by to share a laugh, a selfie, and a story — your voices are shaping the future of our hauora. Every kōrero is being carried forward in our regular reporting and meetings with Te Whatu Ora. We’re listening, and we thank you for trusting us with your truths.

Hauora at home: Everything under one roof in Whaingāroa

Poihākena Marae in Whaingāroa Raglan was the place to be this week as whānau gathered hauora check-ups, hosted by Toi Oranga in partnership with a range of local and visiting health providers. The open-door event invited whānau to drop in, share a cuppa, and check up on their wellbeing — all in a familiar, friendly environment.

Nurses were onsite offering general health checks, alongside a wide range of services including physiotherapy, mirimiri (traditional Māori bodywork), immunisation, cervical screening, and counselling. A Ministry of Social Development (MSD) staff member was also available.

Two Heart Foundation representatives were kept busy with blood pressure checks, while a local GP provided full consultations in a dedicated clinical space.

Having services close to home made a big difference, particularly for kaumātua who often face challenges accessing care, and for younger whānau looking for convenient, supportive options.

“Whānau felt more comfortable at the marae, and not having to travel far — and having everything under one roof in such a friendly space just made sense,” said Megan Tunks, one of our Whānau Voice kaimahi.

Predominantly Māori came, but some non-Māori as well. “They relaxed with a hot drink and some kai, connected with others, and visited different service providers while they waited.”

Many of the visiting providers, including the physiotherapist and mirimiri practitioners, were from the local community themselves — a powerful reminder of the strength and value of community-led solutions.

The kaupapa was simple and effective: bring health services to where whanau already feel safe, respected, and connected. The result? A whānau-first day grounded in manaakitanga, kaitiakitanga, and whanaungatanga— showing what’s possible when hauora is delivered with aroha.

Photo: Lesley Thornley, a physiotherapist and daughter of the late Dr John “Digger” Penman, who served as the local GP from the 1940s to the late 1960s before being succeeded by Dr Ellison; Megan Tunks, Whānau Voice kaimahi with the Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board; and Pablo Rickard, affectionately known as Whāingaroa Raglan’s ‘unofficial Mayor’.

From the Frontlines at Waahi Whaanui: Mental Health and Addiction Gaps

On the frontlines of whānau support, the cracks in the system are becoming impossible to ignore.

This week, our Whānau Voice team visited Waahi Whaanui in Raahui Pookeka-Huntly that was established in 1983 by the Tainui Maori Trust Board as one of its ten Marae Cluster Management Committees that works across a vast rohe — from Mercer in the north, to Raglan in the west, Te Hoe in the east, and Kirikiriroa in the south.

They deliver an impressive range of integrated services: Whānau Ora, parenting support, family violence response, social workers in schools, rangatahi transition services, alcohol and addiction support, and more. Deeply embedded in their hapori driven by a commitment to uplift whānau. But even with all their expertise, one reality stood out: they’re doing critical mahi with our people experiencing a health system under immense strain. The need is growing significantly, particularly for our rangatahi.

Mental Health: Access Denied by Distance and Delay

For Raahui Pookeka based whānau,often access mental health assessment is to travel half an hour to Hamilton. Once seen, they’re referred back to local services in Raahui Pookeka—services that are already under immense pressure.

The latest data from Te Hiringa Mahara – Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission backs this up:

- 16,000 fewer people were seen by specialist services in the year to June 2024, compared to 2021.

- More than 10,000 of them were under 25 years old.

- The drop isn’t because fewer people need help—it’s because they can’t get it.

This is a crisis. Not just of access, but of dignity.

Addiction Support Has a Waitlist—But Pain Doesn’t Wait

There’s a four-week wait to see an addiction counsellor at Waahi Whaanui. For some whānau, that’s a tipping point. There is limited alcohol and drug support for rangatahi under 18. We heard that many rangatahi are in crisis, with no place to turn.

Kaumātua Saving Up Their Pain

Kaumātua said they “save up” their health concerns because of cost and not wanting to be hōhā or overburden already stretched services.

It is not tika that they should feel like a burden. They carry our whakapapa, our mātauranga, our mauri. They should be cherished and prioritised.

The Numbers Are Stark—But Not New to Us

Māori in Waikato are:

- 9 times more likely than non-Māori to be hospitalised for any mental or substance use disorder

- 6 times more likely for schizophrenia

- 7 times more likely for substance and alcohol-related harm

- And an average of 225 Māori (mostly wāhine) are hospitalised for intentional self-harm each year

In Hamilton, over 2,000 Māori aren’t enrolled with a GP—shut out from the most basic preventative care.

Where to From Here?

What we saw was a failure of the health system to support providers like Waahi Whaanui who are under pressure, the increased caseload of kaimahi carrying too much without the resources they need, and whānau trying to hold on without falling through the cracks.

We stand alongside them—and we raise their voices.

Last week the Government announced a $28 million investment over four years in Budget 2025 to shift the response to 111 mental distress calls from Police to mental health professionals. For frontline providers like Waahi Whaanui it will take far more to address the deep gaps in accessibility, workforce, and culturally grounded care.

Te Tiratū is calling for:

Providers to be adequately resourced to cope with the increasing demand on services

- A focus on services for rangatahi under 18 that are locally relevant and accessible

- Appropriate whanau orientated triage processes

- Culturally grounded, local solutions led by whānau, hapū and iwi

Te Tiratū will continue to amplify your voice until the system listens.

From left to right: Rawinia Marsh – Integrated Services Manager Waahi Whaanui Trust, Fiona Helu and Hemi-Lee Morgan – Whānau Ora Team.

Maniapoto rising: “We know what works”

Our Whānau Voice kaimahi and Tumu Whakarae attended a recent hui held at Te Kūiti, hosted by Maniapoto Marae Pact Trust where a strong and heartfelt kōrero unfolded about the state of hauora for whānau across the Maniapoto rohe.

Frontline kaimahi, whānau navigators, and community leaders — including CEO Shirley Turner — came together to shine a light on what’s working, what whānau are asking for, and where the system is falling short.

“Our people know what works — we just need the system to back us,” Shirley said.

Maniapoto Marae Pact Trust offers a suite of integrated health and social services designed to walk alongside whānau, ensuring every door is the right door. These include:

- Kaiārahi Services – placing whānau at the centre, helping them define and lead their own goals across multiple service areas.

- Whānau Direct – offering fast, flexible support when whānau need it most.

- Disability support and mental health services, including social workers in schools.

- Tamariki Ora – a standout success story. The Tamariki Ora nurse and whānau navigator work together in the community, achieving strong immunisation rates despite not receiving equitable funding.

Photo from left to right: Te Tiratū Tumu Whakarae, Brandi Hudson with kaimahi of Maniapoto Marae Pact Trust – Sauaga Poliko, Lisa Kerekere, Rena Morgan, Honour Muraahi, Adrianna Astle and Raven Torea our Whānau Voice kaimahi

The Trust also contributes to Healthy Families Te Kūiti, with locals like Michelle Wi running weekly Māra Kai workshops on preserving, pickling, and food sovereignty — all part of a wider push for long-term wellbeing.

Shirley was clear about how the Trust works, “Whānau are in the driver’s seat — and that’s how it should be. Our services walk with them, not ahead of them.”

Systemic Challenges Undermining Equity

Despite these local strengths, systemic failures continue to undermine outcomes for Maniapoto whānau.

One striking example shared at the hui was of a kuia who was rushed by ambulance to Waikato Hospital with minimal belongings, only to be sent home later in a shuttle and left on the roadside.

It was only thanks to a member of the public contacting a local health worker that she made it home safely. This case highlights the urgent need for a more responsive, automatic travel support process — particularly around the National Travel Assistance (NTA) scheme.

“There needs to be a built-in, automatic system for whānau travel vouchers — not an afterthought.”

Other systemic concerns raised include:

- Falling through administrative cracks in post-hospital care and transport.

- No sustainable funding model for high-performing but underfunded services like Tamariki Ora.

- The need for better wellbeing measurement tools that reflect whānau realities.

- A desire for more regular, locally based specialist outreach, especially for kaumātua and kuia.

Networks and Ngā Kaupapa o te Rohe

The hui also acknowledged the strength of local collaborations — such as the Waitomo Community Health Forum and initiatives like Harvest to Home and Wai to Kai, which focus on food resilience, sovereignty, and wellbeing.

The message from Maniapoto is clear: local, kaupapa Māori solutions are working — but they need resourcing and system-level support.

“We’re seeing positive outcomes because our services reflect the lived reality of our whānau. But without equity in funding and process, our people continue to carry the cost,” said one kaimahi.

National immunisations up as Māori rate treads water

An uptick in overall immunisation rates for infants and young children is to be welcomed, but rates for tamariki Māori continue to lag, says Mataroria Lyndon.

The University of Auckland senior lecturer and member of Te Tiratū iwi Māori partnership board says it is important to recognise progress has been made, “but that does not necessarily reflect the reality for Māori and inequity”.

Data showing alarmingly low immunisation rates, delays, costs still undermining Māori Health

Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board April Whānau Voice Report mirrored by Te Whatu Ora data has evidenced immunisation rates 33% lower than the national average, widespread inequities, long wait times, and unaffordable care still plaguing whānau Māori in its Tainui waka rohe.